Posted by Nick Brook 08 September 2024

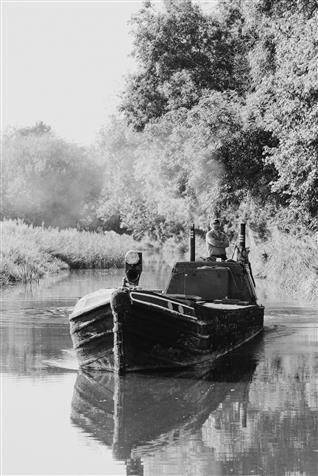

A mainstay of the English folk scene for nearly two decades performing with Pilgrim’s Way, Gren Bartley, James Kerry, Albireo and a number of others, Tom Kitching has been developing a reputation in his own right as a fiddle player and writer of both tunes and prose. His third book and album of the same title Where There’s Brass tells the story of 6 months spent living on a former oil barge on the waterways of London, and with it the history of the canals over the last half century.

After reading it, we were keen to find out more about the link between his life as a working musician and his other passion of narrowboating. He was kind enough to take the time to answer our questions, and then some! For the enjoyment of Bright Young Folk readers, Tom Kitching...

It sounds like you learnt a lot about both boating and fiddle playing watching and working with older generations. What was it that drew you to folk fiddle and spending your teenage years in pub sessions in the first place?

Big question to start with! I was something of a socially awkward teen, and not particularly academic either. Playing the fiddle was something I took a lot of comfort in at what was otherwise a difficult time in my life, and I became somewhat obsessed.

Friday nights at the Harrington Arms in Gawsworth became my focus. I didn’t get great A-levels, but got a good grounding in the tradition, learning by ear. I’d made a start on the violin at school and not really got very far. I simply wasn’t motivated to practice until I discovered the session, when I was 16, but at least I had some basics to build upon.

I’d always had an awareness of the tradition. My parents listen to a lot of traditional music, and my mum is a mandolin player, so the shapes and forms of the music felt very natural in a way that the classical repertoire never did to me.

You and Marit Falt must be the only professional fiddle and lätmandola duo performing on the English scene! How did you start working together?

I was a tutor at the Folkworks summer school in Durham in 2013. As part of this, I did a concert at the Elvet Church, opening for Vamm, a trio featuring Catriona MacDonald, Patsy Reid, and Marit. I remember the sound of the mandola ringing round and filling that fabulous space and thinking I’d never heard anything like it.

I had plans to make a solo album but wasn’t sure how to make it sound really different and original. As soon as I heard Marit I knew I wanted to work with her. She’s the best musician I have ever met.

The album is your third together, and the first to be made up entirely of newly-composed tunes. Was this a conscious choice or just the way things panned out?

Very much a conscious decision this time. My eight pieces are all so tied to the waterways and my experiences on them. Many of them are built around rhythms and shapes taken from particular soundscapes I encountered. South Island directly reflects the cross rhythms of multiple Bolinder engines overlapping.

Marit’s contributions really seemed to fit the mood of the album too. Shoulders of Giants is dedicated by her to Sandra Kerr, but the idea of how much we owe to the great people who blazed a trail before us is a central theme to the book too. This direct interrelatedness between music and story really supports the live performance, as the two elements can overlap seamlessly.

Your book does a good job giving the reader a sense of the craft involved in boating. What takes longer to master: carrying a tune on the fiddle or smoothly navigating a flight of locks?

I have mastered neither and woe betide anyone who thinks they have! In both fields I am aware of the extraordinary pool of knowledge, polished and practiced by so many generations, from which I am lucky enough to draw.

As I hit the statistical middle of my life, I am increasingly aware that my role is slowly pivoting to passing on as much as I can. I would say on balance that I am a better boatman than I am a fiddler, simply by dint of having started earlier in life, although my knowledge is fairly specific to my boat, Spey, and I am far less experienced at working pairs, especially on long lines, and with horse boating.

You seem a natural at travel writing. Did you always have an ambition to be an author?

Yes! I was writing before I took up playing. As a mid-teenager I wrote a novel. It was terrible! But it taught me a lot about writing, and I had a very kind English teacher called Mr Spence who was always prepared to read what I wrote and offer feedback to me.

I’m not very visual, preferring to document the world through words and sounds instead of the ubiquitous photograph. I travelled to China five times in my twenties, initially on photographic rail tours, and the other participants found it bizarre that I preferred to just soak it in and write in my notepad instead of photographing everything that moved, and I quickly came to realise that such trips offered a way into a much bigger story of industrial and societal change.

My travel writing has followed this format; using a relevant artefact to explore or interrogate something deeper. From deploying the English tradition as a busker to dig down into England and its understanding of itself, to using a historic working boat to piece together the past, present, and future of the waterways and knit it together.

I have always kept travel diaries and love the works of writers like Eric Newby and Dervla Murphy. With the search for the exotic having brought every distant corner of the world into our living rooms, I find my inspiration instead at the end of the street in those places that are so easily dismissed as too near, too dull, too unimportant. This also suits my budget. Pan haven’t reached out with that massive advance just yet, so I have to do it all myself on a shoestring.

Considering how vital they were to the economic life of the country at one stage, there doesn’t seem to be that many songs in the traditional folk canon about those working the canals as say, miners or farmworkers. Why do you think this is?

This is a question that has been asked a number of times before and deserves a long answer. In the late 1960s, the BBC commissioned David Blagrove to record the music of the waterways, and so he set out with his field recorder.

He found that the waterways community didn’t really have a musical tradition of their own, so he collected a lot of soundscapes and boaters telling stories of their lives and interwove that with some of his own songs. The BBC waterways album Narrow Boats (1969) is the result and it’s an extraordinary piece of work and a window on a hitherto unrecorded world.

Reading through the handful of books about life on the working waterway, my suspicion is that there may have been rather more music in earlier times. Early canal writers sometimes mention of boaters playing squeezeboxes at the end of the day, frustratingly without giving any clues as to what they were actually playing.

The advent of the motorboat led to much longer days being possible. A horse must rest, so a leisurely evening after work might be possible, but the Bolinder can run into the night, and Tom Rolt laments in Narrow Boat (1944) how the experience of the boater became one of the grind, dawn to dusk, paid by the load, and free time was between trips rather than during them. If there was a particular waterways musical tradition, it died out with the motorboat.

There are virtually no books by the boating community themselves. Early books like Flower of Gloster(1911) and A Caravan Afloat (1916) by E. Temple Thurston and C.J. Aubertin respectively offer a small window on the communities and ways of working on the canals in the days before the motorboat but are written very much from an entitled outsider’s perspective.

It is not until the Second World War, and the ’trainee’ programme that brought educated middle-class women in to plug the shortage of workers that anything is written remotely from the perspective of those who worked the water. Books like Troubled Waters by Margaret Cornish, Maiden’s Trip by Emma Smith, Idle Women by Susan Woolfitt, documenting this wartime work are essential reading. Even then, they are still outsiders in this world. The Amateur Boatwoman by Eily (Kit) Gayford is perhaps the one that gets closest to the heart of it, as she was already a boater and became a trainer on the scheme when it was set up.

It is easy to forget the extent to which the narrowboating community were looked down on by society. Industrial workers in many other fields became celebrated as heroic characters, and the innocent, pastoral England as selectively showcased by so many folk songs was a deeply attractive foundation myth to the gentile Victorian folk scholar. The boating community fell between these two stools, being othered as ’water gypsies’ and treated with suspicion.

Neither a reminder of our bucolic past, real or imagined, nor a heroic worker, driving us selflessly into prosperity, although ironically, they were perhaps a rare community to truly be both. It is a reminder of how our prejudices so strongly shape those whose culture we consider important and those whose culture we do not, and consequently it is likely that much material was simply not collected or preserved. Many boaters, upon leaving the water at the end of the carrying days, disguised their background out of a sense of shame.

Until the leisure age of the waterways began in the 1970s, there was virtually no public interaction with the canals. Almost everyone has ridden a passenger train and been in a car on a road, but the working waterways were almost exclusively for cargo. Where familiarity bred enthusiasm and celebration, this unfamiliarity and disconnect with the waterways bred suspicion and fear.

Waterways workers were othered as being a group apart, widely perceived even as a distinct ethnic group, and without any meaningful voice of their own with which to reply. Disused waterways were filled in during the 1960s as a moral panic that children would fall in and drown swept the nation. The country was keen to bury the story of the waterways, literally.

It took groups of enthusiasts to save as much as they could, and that’s another big theme running through the book. The graft and politics that were needed to create a new future and vision for the waterways and totally recast them as a force for good and a big part of the leisure industry was huge and a massive triumph.

These groups of modern navvies often had their own songbooks and brought music back to the canals. They had finally become something that could be celebrated through song and music again. It is hard to overstate just how massive and profound this reversal of society’s sentiments towards the waterways has been.

Since these days of restoration, an increasing number of artists have turned their attention to the waterways. As a teenager I saw Jeff Dennison and Benny Graham performing their show They’re Coming Back to The Water, as well as seeing the much too quickly departed Buz Collins. Rhiannon Crutchley is a travelling boater and a fabulous singer and musician performing material that bridges the generations with aplomb. Nancy Kerr’s famous song Queen of Waters exemplifies this new relationship with the water we are forging as a nation.

But as ever, it is a contested space, with many of the old prejudices finding fertile new ground in the othering of those new waterways communities forming out of economic necessity. Perhaps the most central question of the whole Where There’s Brass project is "who are the true inheritors of the waterway?’ The weekenders and enthusiasts or the people who live it day by day?

This first group have the skills and understand their place in the golden thread of knowledge, whilst the other have the day by day lived experience and their finger on the pulse. A problem with the waterways is an annoyance for the first group but a disaster for the second.

What I have tried to do is present the case that the modern waterways community is a vital chapter in the history of the waterways rather than a standalone phenomenon. The sooner we recognise that and work together to guide the waterways to a place where all groups work together, the better for all parties.

People once travelled the waterways on boats such as Spey primarily to earn a living, whereas now the canals are seen by many outsiders as a place of leisure. Do you worry a similar thing could happen to musicians who travel the motorways for their livelihood?

The pace of technological change is breathtaking. The days of the trucker might be numbered. We will always need to travel, and it makes sense to take the music to audiences rather than the audiences to the music, so I don’t see that changing, although I have speculated as to which might become Britain’s first heritage motorway.

Very much hoping that isn’t the case - have you got any more journeys planned for us to read or listen to tunes about?

I’m taking the summer out after this tour to decompress a bit. It’s been a huge haul to complete a book, an album, programme a tour, and do all the publicity myself. I don’t know what will be next, but my projects usually just become clear to me, rather than being something I sit down and contrive. One day I just realise that this is something I should do. I am completely without commitment and tie, so it could be anything.

Looking forward to hearing about it! In the meantime Tom’s website tomkitching.co.uk is an ideal place to find out about his projects past and present and pick up a copy of Where There’s Brass in book and album form

(photography by Elly Lucas)

See all of Bright Young Folk's text interviews.